The Nazi Drawings (1961-1971)

33 drawings

Mauricio Lasansky working on The Nazi Drawings in his Vinalhaven, Maine studio. 1962

Dignity is not a symbol bestowed on man, nor does the word itself possess force. Man's dignity is a force and the only modus vivendi by which man and his history survive. When mid-twentieth century Germany did not let man live and die with this right, man became an animal. No matter how technologically advanced or sophisticated, when man negates this divine right, he not only becomes self-destructive, but castrates his history and poisons our future. This is what The Nazi Drawings are about.

- Mauricio Lasansky, 1966

The Nazi Drawings examine the brutality of Nazi Germany. They are a powerful expression of the profound disgust and outrage Mauricio Lasansky felt after viewing a US Military documentary showing the victims and aftermath of Nazi atrocities.

The artist worked intensively for six years to create the series, which consists of thirty individual pieces and one triptych. The drawings were created with lead pencil, water- and turpentine-based washes, and collage on common commercial paper. "I tried to keep not only the vision of The Nazi Drawings simple and direct but also the materials I used in making them. I wanted them to be done with a tool used by everyone everywhere. From the cradle to the grave, meaning the pencil. I felt if I could use a tool like that, this would keep me away from the virtuosity that a more sophisticated medium would demand."

The figures in the drawings are life-size and larger in dimension.

Since their completion, The Nazi Drawings have been exhibited in many prominent art museums, and have received widespread public attention. In 1967, The Nazi Drawings, along with shows by Louise Nevelson and Andrew Wyeth, were the first exhibits installed at the new Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

Lines wrapped around the block with people awaiting entrance to the exhibition. Articles were published about The Nazi Drawings in Time and Look magazines as well as The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. The Nazi Drawings continue to connect on a highly visual and deeply emotional level with observers of all ages.

The Richard Levitt Foundation purchased The Nazi Drawings in 1969, and they now reside at The University of Iowa Museum of Art. They continue to travel to other museums every few years and occasionally can be seen on display in the Lasansky Gallery at the Museum.

In the Fall of 1997, Iowa City filmmaker Lane Wyrick, in collaboration with Phillip Lasansky as content advisor, began The Nazi Drawings Documentary project with grants from the University of Iowa Foundation, Richard & Jeanne S. Levitt of Minneapolis, Marvin & Rose Lee Pomerantz of Des Moines, and Webster & Gloria Gelman of Iowa City. Filming and production continued for three years, and in April of 2000 The Nazi Drawings Documentary premiered at the Levitt Center for University Advancement in Iowa City. Information on the documentary, and additional background and history on drawings themselves, can be found at The Nazi Drawings Web Site.

The images below are a complete presentation of The Nazi Drawings in sequence, including the final "Triptych" completed in 1971.

Photography courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

-

The interpretative text below each of The Nazi Drawings is taken from the text and images of the The Nazi Drawings, a catalogue published on the occasion of the premiere exhibition of The Nazi Drawings held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1967. During the same year the exhibition traveled to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Des Moines Art Center in Des Moines, Iowa. These drawings by Mauricio Lasansky were subsequently exhibited at the Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City (1969); The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City (1970); and Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania (1974).

Through an extended loan agreement with the Richard S. Levitt Foundation of Des Moines, The University of Iowa Museum of Art is the repository for The Nazi Drawings. When they are not on tour, the drawings are housed in a special gallery of the University Museum.

This series of drawings, in preparation over a period of five years, was completed in the summer of 1966. The images are arranged in the tour sequentially. The text that accompanies the drawings is drawn from Professor Edwin Honig's original text created for the exhibition catalogue. In addition, the on-line tour includes the three panel "Triptych" completed in 1967 (which appears between drawings #29 and #30).

-

Rarely can the artist put down in his own medium an imaginatively mature vision of his time that is made up of his own experience and also actively invokes the experience of millions of his contemporaries. There is something special about such an art, and something special about the response it calls forth. Whatever else it may be, such an art is an act of partisanship—it takes sides in a very personal way. As a document it also stirs the partisan feelings of its beholders. Bosch, Goya, Daumier, and Picasso created overpowering artistic documents of this sort, charged with the artist's most personal and most mature idiom.

As his contemporaries we should not find ourselves at ease with what Mauricio Lasansky has done, if only because the subject of The Nazi Drawings is a part of our past that still disturbs us. Yes, we can pass them by and look elsewhere, or we can stare at them, examine them with fascination. Whatever we do, the drawings will continue to disturb us. And no wonder, since they constitute such an awesome rendering of our times—our worst historical experiences reduced to basic terms of manmade slaughter, innocent suffering, erotic and religious demonism, and these recorded in the simplest medium an artist can use: lead pencil, earth colors, turpentine wash, and a common commercial paper.

Looking with shock-fascinated eyes at the drawings, it comes to us that we are the prurient observers, the guilty bystanders who survived these terrors of human history. We have survived, but at what price, with what knowledge and understanding of our own participation in events now rigidified in the nightmare of the past? Now that those events have become matters of innocent curiosity to human beings born since, we keep wondering how we could continue in silent anguish as survivors of that period all these years.

There is no answer. One can only say that to the young, forever being born, we are the living reminders of the Nazi concentration camp era. The way we smile, our gestures, our turns of speech, the very lines of our faces, still bear witness to the terror, grief and guilt (including relief from terror, grief and guilt) that culminated with the Nazis. It is a piece out of our own lives and past that the artist of these drawings is recording. How can we then expect him to be gentle and comfort us if he is to be honest—that is, if he is to represent what happened, what is still visible in us, with the total imagination of what it takes to be a man?

These drawings were made by a committed human being, and artist advocating the truth of the total imagination. This means that his art is illustrative because it represents the truth, and representative because it is moral and dramatic.

From first to last the drawings enact drama that presupposes something like a documentary series of events that actually took place. These are the events that occur again as we look at the drawings. Reality becomes what is being done to and by human beings, not why it is being done, in the drawings; from our critical view of this it follows that to do what is being done here entails the loss of all human and spiritual values. As in any drama, getting at the sense of the action means putting ourselves behind the eyes not of the actors but of the creator, seeing and feeling what his language tells us he has seen and felt.

Lasansky is a survivor who in his drawings is still there, in the Nazi camps, so that we view his work as a continuing rehearsal of the drama of what it means to have survived that experience. We see it with him in the demonic halflight between living and dying—and this is the central condition in all the drawings—where there is little difference between being alive and being dead.

To understand the drawings is to discover precisely what is going on in them—that is, to see them as a pictorial drama of death and human deprivation, from which we have even now barely recovered, unfolding scene by scene, in the numerical order the artist has designated for them. Also, we must understand their dimensions, for almost all the drawings are quite large; roughly six feet high by four feet wide. The exceptions are the first four portraits (of Nazi killers) and a concluding group of five portraits (of agonized infants). In each instance Lasansky insists on the human scale, thereby making his subjects quite literally life-size. In this way their physical scale helps to embody the dignity and horror the artist is committed to dramatizing in the drawings.

The Nazi Drawings (1961-1971)

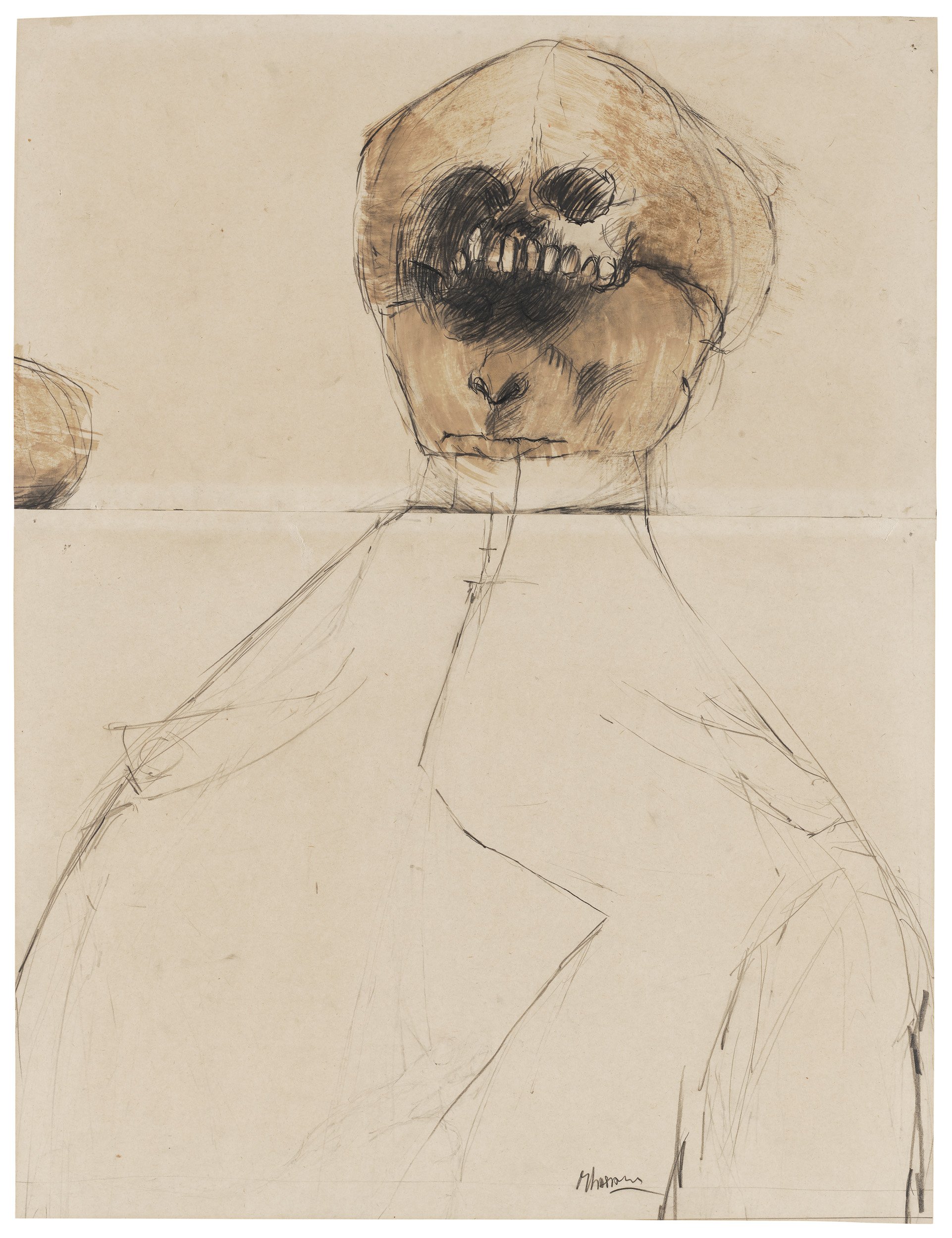

No. 1 (1961)

23½ × 23¼ in. | 59.7 × 59.1 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine wash, on card paper

The first four drawings are introductory, forming a gallery of heavy-headed, skull-helmeted busts seen mainly in profile; these figures come to be associated with the executioners of the innocents in later drawings. In the first, the skull helmet suggests the German visored military campaign hat. The neck, shoulders and chest, all encased like a sausage, further suggest an entombment in clothing, a condition of being half-buried in life.

No. 2 (1961)

23 × 23½ in. | 58.4 × 59.7 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine wash, on card paper, with torn edges

The same motif is continued in the second drawing, with the skull-helmet raised a bit and the teeth knocked out. There is also the beginning of the typical dark-penciled weblike lines swaddling the face and bemedalling the chest over the tracing of a hand lying inert like a dead spider.

No. 3 (1961)

23⅜ × 22½ in. | 59.4 × 57.2 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine wash, on card paper

The bulging sausage-necked man reappears in the third drawing. Except for the grotesque proportions of the head and neck, the rendering is deliberately sketchy, although new details are beginning to crop up, such as the grimly developed, cadaverous, half-hidden face, the hatchet nose, and the dark penciling around the eye—signs of the killer.

No. 4 (1961)

25¾ × 19¾ in. | 65.4 × 50.2 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine wash, on card paper, two sheets

In the fourth drawing there is more detail because we have a three-quarter frontal view of the head. Also a new motif appears here: the cut-off drawing paper pasted together just under the collar of the uniformed figure—half-military, half-clerical. Floating free on the left margin is something that looks like the skull of a baby in profile; and, barely visible on the front of the Nazi's uniform, are the tracings of an empaneled religious figure or nude.

No. 5 (1961)

68½ × 22¼ in. | 174 × 56.5 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, on card paper, two sheets, with some torn edges

The fifth drawing is the most pictorally developed thus far. The full-length figure in profile—a straining bemedalled Nazi in uniform but without pants—is gruesome despite his humiliating, comic stance. His naked leg shows, he is heiling, and he is strangely bonneted, almost as though he were being protected from the sun (the figure's ironically abbreviated uniform suggests the tropics), with a huge bovine skull whose immense teeth are drifting away from the forehead. A bloody earth-tinged color suffuses his swastika armband and the left fist clenched behind his back, while from the rigidly upraised right hand the same thin gore obscenely drips.

No. 6 (1961-1966)

70⅝ × 22⅞ in. | 179.4 × 58.1 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine wash, on card paper, three sheets, with some torn edges

In the sixth drawing the trend to greater pictorialization increases. Here, the by-now quite variously and intricately depicted skull-helmet sprouts skeletal limbs. The upper part is like closed wings, emerging from the cocooning ribcage, while the lower limbs are placed jauntily astride the booted and uniformed figure. The figure itself is hardly visible except for the grimly locked three-quarter profile within the pillbox opening, formed by the skull's half-jawed roof under the teeth. Only the skeleton is filled in color.

No. 7 (1961-1966)

76½ × 22⅛ in. | 194.3 × 56.2 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine wash, on card paper, three sheets

The intricate culmination of earlier motifs becomes powerfully apparent in the next drawing where a semi-nude woman is portrayed full-length in profile: heavy-penciled swaddling lines envelop the skull-helmeted head—like a spring bonnet with teeth for flowers—and the woman's hair becomes a gross entangled nest out of which the sagging face half emerges, patched on the eye. The melon of a naked breast rests on a filmy, crumpled shift that is being held up by hands clasped together on the bare belly, while one hand and forearm are again heavily penciled to depict the webbing of a long glove. This motif is picked up again in the splotch of pubic hair and the boldly irrelevant stockings and high heels. It is apparent that the whole figure is cut off and pasted together in three sections, as if to call attention to the factitious and tawdry nature of what is being exhibited.

No. 8 (1961-1966)

69 × 25½ in. | 175.3 × 64.8 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, on card paper, three sheets, with some torn edges

Elaborated motifs grow more profuse in the next dozen drawings—the central and most highly graphic part of the series. The eighth drawing shows a frontal view of another half-dressed prostitute figure, perhaps the same figure as in the previous one. Out of her bald, moon-shaped head she smiles slightly, half leering, her eyes lost in nimbus of darkly penciled fuzz. With arms and hands raised in the appropriate gesture, she reminds us of a woman trying on a hat. There is a kind of web thrown over her shoulders, merging into the oversized man's jacket she is wearing that half obscures her small rounded breasts. As before the sections of paper are crudely cut off and pasted together at the thorax. In these details, reinforced by the thickly bulging upper thighs mounted on much narrower thighs and well-modeled legs in high heels, we get the impression of a slyly posing hermaphrodite, narcissistically flaunting its professional stock-in-trade.

No. 9 (1961-1966)

68 × 24 in. | 172.7 × 61 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with touches of red chalk, on card paper, three sheets, with some torn edges

In the ninth drawing the moon-faced prostitute reappears, embracing the truncated outline of an army sergeant. Smiling, she wrenches herself around, almost swirling with the weight of the skull-helmeted soldier she is clutching, the rhythmic patterning of heavy penciled swaddling material now plainly repeated in her hair and webbed eye under the skull-helmet bonnet she wears, and again in her long-gloved, supporting left forearm, her waistband, her stockinged legs, her lifting high-heeled shoes. In the commotion her slipped-up bra, shown from the back, and the slight blood-colored dabs raining down from her waistband help to mark off the crucial zones of body truncation.

No. 10 (1962-1963)

73 × 44½ in. | 185.4 × 113 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, on card paper

Having displaced the sergeant, a curiously angled, self-bracing skeleton appears in the next drawing. It has mounted the prostitute from behind and is both biting her face, while resting one arm on her shoulder, and clutching her pubic area with a long extended arm. The complementary light-and-dark areas are also intruded on by the swirling tubular brown turpentine wash.

No. 11 (1961-1966)

73⅞ × 44¾ in. | 187.6 × 113.7 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with touches of red chalk and green pastel, on card paper, with some torn edges

The eleventh drawing reveals the still leering but almost totally darkened prostitute figure wreathed in something like heavy black yarn. She is seated cross-kneed, extended over the bony laps of three merging skeletons, all encased like ghostly sausages. Around their obscured faces are interlacing lines of well-defined teeth and rib bones, rising and falling like arpeggios. There is a complementary motif in the more lightly drawn faggots of fingers and hands that seem to separate one tightly pressing figure from another. An irrelevant forearm hangs down from the top, fingers coyly splayed over a bill of paper money.

No. 12 (1961-1966)

71¼ × 44¾ in. | 181 × 113.7 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, on card paper

In the twelfth drawing a severer pose of the same prostitute, with enormously outspoken breasts and buttocks, is contrasted to the heavy, black, beetle-backed, spider-legged skeleton clutching and furiously biting her flesh, one arm and hand pressing tightly down, half for support, half out of intense passion, the skull-helmeted bonnet jammed over her twisted face, her playfully averted head.

No. 13 (1961-1966)

75⁵⁄₁₆ × 45 in. | 191.3 × 114.3 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with touches of red chalk, on card paper, with some torn edges

It becomes evident at this point that the drawings are intended to be "read" as one would read a cartoon serial. Seen in this way, the thirteenth contains most of the motifs that have thus far appeared in the others; also, there are new motifs. Dominant once more is the prostitute figure of the last six drawings, now pathetically strung up like a side of beef, her naked haunches, back, and thighs displayed, her hands clasped together, perhaps in prayer, somewhere above her completely disheveled hair, seen from the rear like a tumbled nest. Her shift, sadly fallen around her thighs, is being held up idly by a blackened, encased executioner figure to her right. The figure also concentrates in himself the previously introduced motifs of ambiguous perching bird, embracing skeleton, skull-helmet surmounted by an overarching pillbox out of which the skeletal teeth twinkle, the facial features barely discernible. Additional pairs of hands and forearms appear in the lower portion of the drawing, one apparently holding a skeleton head looms up to the left, grinning out at the spectator beneath vague tracings of another female figure strung up to the left of the former one, perhaps suggesting in this way an ad infinitum series of the same kind of victim. A tracery of heads and infant skulls, giving random sense of abandoned, snuffed out lives, seems to glow transparently through the lower portion of the drawing. The pose of the figures here strongly recalls the graphic idiom of Goya's Desastres de la Guerra.

No. 14 (1962-1963)

73 × 43¼ in. | 185.4 × 109.9 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine, on card paper, with some torn edges

In a particularly macabre arrangement of figures, the fourteenth drawing gets its effect from the hard chiaroscuro contrasts noted before with an intensification of the familiar motifs of skull-helmet (here slipped down over the executioner's head until it covers everything but the chin); the squatting, exhausted (or preying) skeleton bending with ballooning head balanced acrobatically between dangling arm bones over the back of the inclining executioner; and, finally the half dead child, whose eyes and head are being miserably cracked between the strong thick hands of the executioner, desperately, irrevocably. Perhaps it is the voluminous density in the drawn figures, their physical grossness, that makes for the horror of this drawing, despite the simplicity of its rendering.

No. 15 (1961-1966)

65 × 45 in. | 165.1 × 114.3 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, on card paper

If one can separate dream from nightmare, the next drawing would seem to be, by contrast with the others, the most dreamlike so far. The dancing or hopping little girl in the foreground is the lowest figure in the pyramid of four topped by an overarching, perching skeleton under whose top jaw appears inset, like a cameo, the face of the dark maternal figure, her dress filling most of the drawing. On her right shoulder she supports a bloated infant's corpse with distended belly and fragmented legs stretched stiffly out toward the left. The group is peering into the near distance—who can say with what expression—while behind them are the corner posts of a concentration camp fence. Vague pencilings to the right of the skeleton's head extend the fence out of the frame, where the skeleton's arm is pointing to something going on in an area which we cannot see.

No. 16 (1963) If one were not so familiar by now with the skull-helmet motif, it would seem simply a trick of the eye to discover that the crouching skeleton's head is on the executioner's shoulder inclining toward the dead woman (or child, or prostitute figure)—that is, the skeleton is sharing the same head with the executioner. In the sixteenth drawing the simple chiaroscuro patterning is again a sufficient device to dramatize the severity and grimness of the representation.

71⅛ × 43⅛ in. | 180.7 × 109.5 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, on card paper

No. 17 (1963) Again the hanged or gassed figure appears; it is, in fact, the same dead figure of drawing sixteen. But now the number of victims has proliferated to five, with the grotesque perching skeleton sardonically tinkling the censer bell over them all. The irony of the exact duplication of skull helmets on the skeleton and the dark executioner is further upheld in that both have gas mask hoses dribbling down their chests. Like the heiling, bemedalled figure in drawing five, the posturing executioner is here shown with his pants down (actually, they have been slipped down), a farcical, burlesque comment, again, on the cruel absurdity of the brain-locked murderer. Also coming into prominence here in the seventeenth drawing is the transparency effect of crossbars, earlier discernible as fence posts or as extensions of the shoulders and arms of the crouching skeleton.

74⅞ × 44⅞ in. | 190.2 × 114 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with splatters of red wash, on card paper, with torn edges

No. 18 (1963-1966) In the crudely blood-bedaubed collage of the eighteenth drawing, the cruciform motif takes precedence, leaping to the eye with a force that is hard to account for. Not only is the central maternal figure clearly shown being impaled by the newsprint cross, but there is also an arm, either her own or a disembodied one, visible below her terrible head and pulling the string that is hoisting the pop-eyed figure up on the cross. At the same time, as if unaware of the horror, the infant lies on its mother's belly—asleep or dead, it is hard to tell which. In another refinement of motif, the crossbar is here made into a newspaper collage with a clipping in it about an actual SS killer named Kaduk.

75⁵⁄₁₆ × 45¼ in. | 191.3 × 114.9 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine, red and white wash, torn and pasted newsprint, on card paper

No. 19 (1961-1966) Nineteen is another terrifying and complex drawing which skillfully employs the chiaroscuro effect. A swarming demonic presence fills the upper quarter section of the drawing with skull teeth protruding and arms wrapped over a crossbar holding up an emaciated woman victim, scarcely more visible than the concentration camp number etched on her skin. The dangling woman is being preyed upon by the whirring and perching falcons, more clearly behaving here like vultures than like the curious doves they appear to be in the earlier drawings. The birds have nested in the body of the dead and are pecking at the body organs and sucking out the juices. The tracing of a cruciform background emerges sharply in the light earth color that transparently fills the section diagonally down to the bottom edge of the drawing.

76 × 44⅞ in. | 193 × 114 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine, red and white wash, on card paper

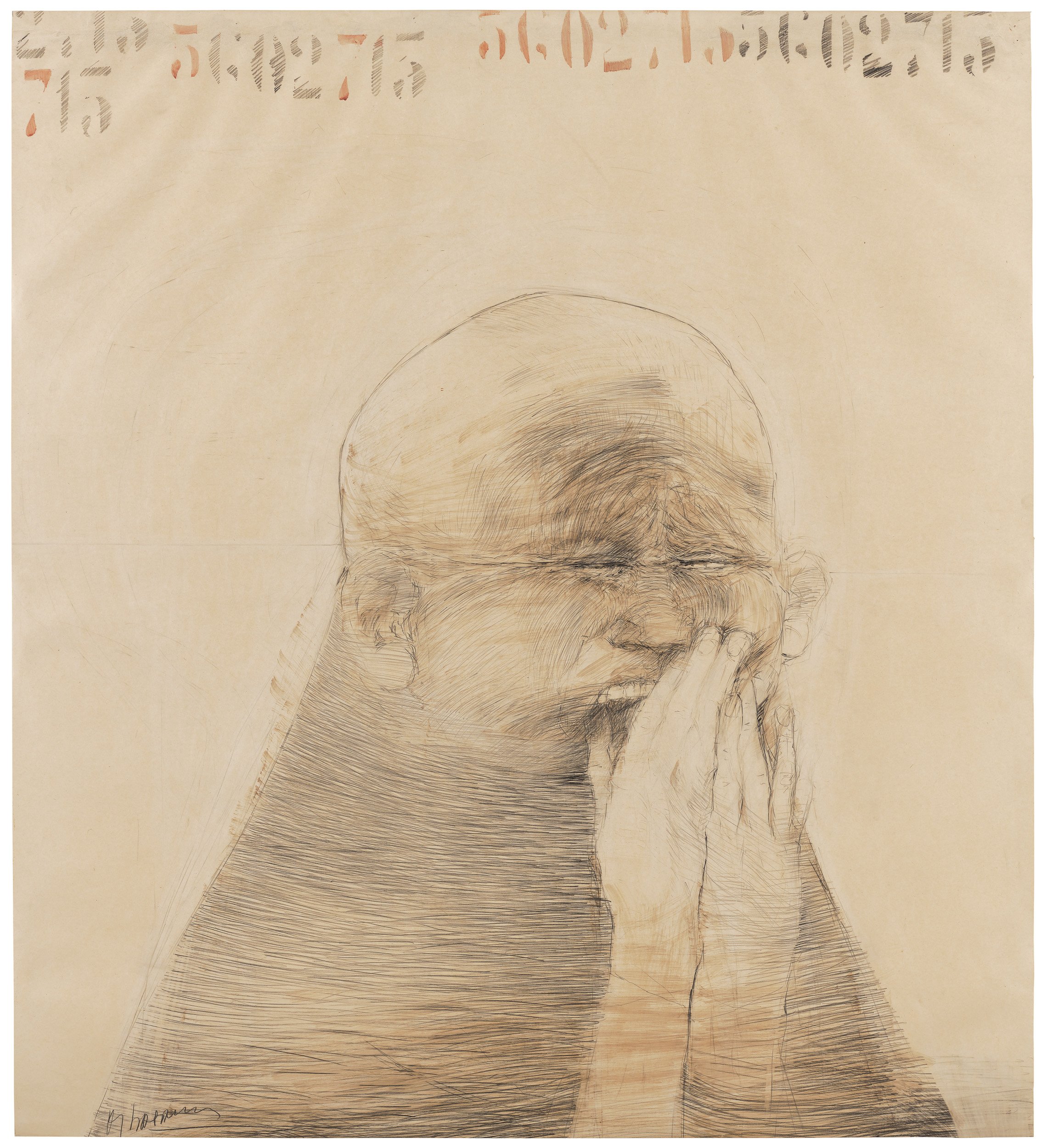

No. 20 (1961-1966)

74⅞ × 46⅜ in. | 190.2 × 117.8 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, tape, stencil, and cut, torn, folded and pasted biblical scripture and paper, on card paper

Collaged excerpts from Judges 15; 1 Kings 4-6, 11-12, 14-15, 16-18; 2 Kings 2-3; Psalms 25-27, 30-32, 139-40, 143; Proverbs 25-26; Ecclesiastes 6-8; Isaiah 1-5, 8-9, 12, 16-19, 29; Baruch 4, 6; Acts of the Apostles 17-18

With the twentieth drawing a new kind of motif proliferation occurs—the concentration camp numbers, repeated in drawing after drawing. The collage print through which the naked victim has been thrust is made up of pages out of the Book of Samuel. And the shadows the figure throws, together with the shadows thrown upon it, show a clearly gradated range of variations on the basic chiaroscuro—something like a monochromatic scale—an effect not prominently exploited until this drawing. What emerges so forcefully then is a classic delineation of the dignity of the human body brutalized by man's perversity—somewhat like the gored spectators in a Goya print. This brutalized figure of a woman raped and impaled, in her last agony of stiffened and twisted hands and feet, with the knobby protruding joints of the starved body, becomes a figure not only of the slaughtered innocents and the suffering martyrs of the past, but of the modern everyman, the killer and the victim both, which each of us actually is.

No. 21 (1961-1966) In twenty-one there occurs what might paradoxically be called the apotheosis of the demonic. A cryptic nightmare figure is loosely enveloped in a swatch of human skin, the tattooed concentration camp number still displayed across it. Behind this human remnant the self-engrossed monolithic shape is laboriously attempting to lift the monstrously heavy skull-helmet that has slipped over its features. At the same time, the phylacteries on the figure's forearms indicate the Jew in his ritual morning prayer. The stippled front, the pubic hair, the heavy earth-colored thighs, the tracery of figures and human features superimposed on, or transparently underlying, the main figure, suggest an overlapping of fact and dream, perhaps an aftermath of silence when the horror of what has happened begins to dawn, and there is the first startled attempt to face it.

70 × 35 in. | 177.8 × 88.9 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with splatters of red wash and touches of red chalk, on card paper, with torn corners

No. 22 (1964-1966) Beginning with twenty-two, and proceeding through all but the last of the drawings to follow, Lasansky focuses on the irreconcilability between the slaughter of the innocents and the unaiding witness of the established church. The transparencies of superimposed and abutting elements in the composition form one commentary upon the subject. Another commentary is the figure of the facing bishop which dominates the drawing with his haunted—terrified or guilt-ridden—features and the splotch of pencil shading running up into his mitre. Barely visible on his cope are the conventionalized stained-glass figures of Saviour and Virgin, standing for the church, while all over this cloth bloody handprints are scattered. Behind the bishop's cope appears the cross on which the torso and stigmatized limbs of a crucified man, a bulbous-headed infant corpse is awkwardly propped, a fragment of its concentration camp number still dribbling down its chest. The assuaging note of a second stigmatized hand intervenes from the upper left side of the frame, gently supporting the infant's lapsing head from behind.

72⅞ × 45⅛ in. | 185.1 × 114.6 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with touches of red chalk, on card paper

No. 23 (1964-1966)

66⅞ × 45¹¹⁄₁₆ in. | 169.9× 116 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine, red and white wash, with touches of red chalk, cut and pasted biblical scripture and paper, on card paper, torn at right corners

Collaged excerpts from Genesis 44-48; Exodus 1-4,8-10

The aftermath to the slaughter, as in a nightmare, silently magnifies the act, dinning it into the consciousness, and bringing the same figures back. And so in the twenty-third drawing they reappear: the bishop with the horror slowly disappearing from his face and giving way to a guilt-evaporating incredulity, and the infant corpse held shield-like against his chest. The dead infant with a skull-helmet covering its features has clearly become identical with the Christ figure it had been merging with in the previous drawing. The falcons have returned to perch symmetrically, un-menacingly, at four corners on the two crossbars. The bishop's cope is a collage made of pages out of Exodus, the same pages that line his mitre. The common portrayal of sex, death, and religion, so heavily intermingled in the other drawings, appears again here. Our eyes snag on the pubic zone distortion under the child's bloated stomach and on the small nude female figure sketched into the upper crossbar on the right, just beneath the bird.

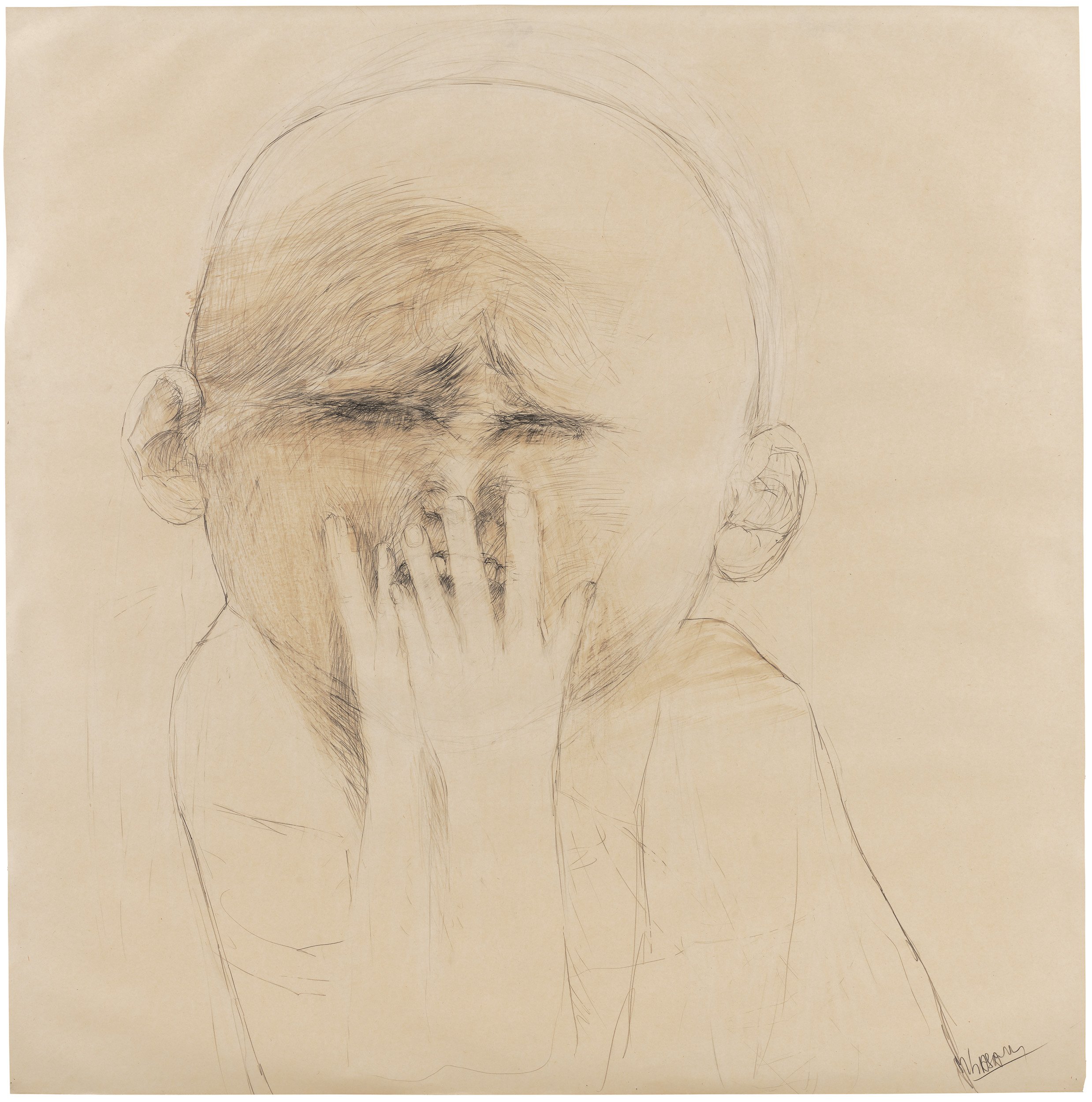

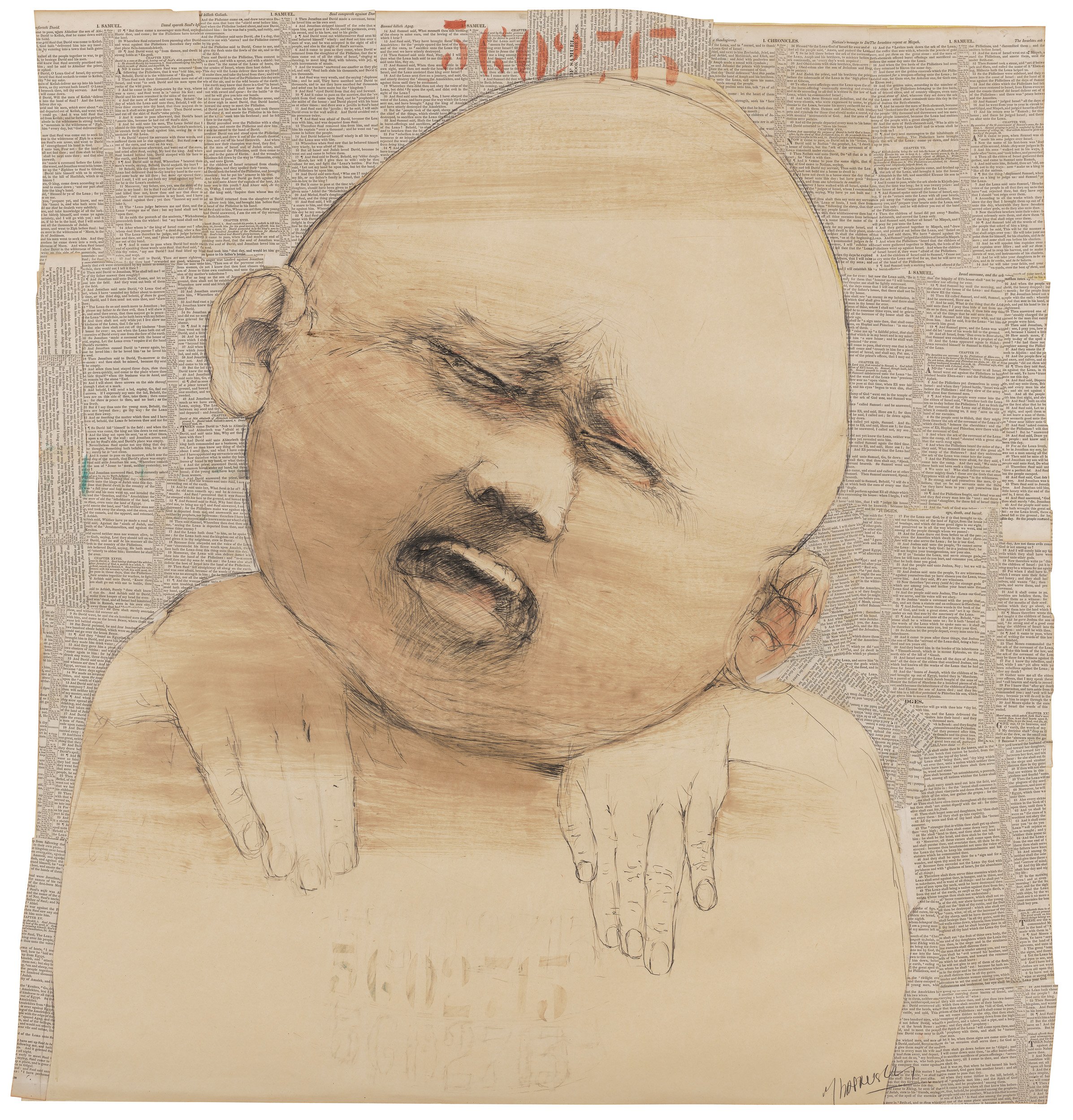

No. 24 (1961-1966) A final series of five portraits begins with the twenty-fourth drawing, and those are the counterparts to the solemnly murderous, skull-helmeted, encased killer figures introduced in the first four drawings. Here the victim children are caught in the midst of their terrible grief and final suffering, with swollen heads enlarged against their small, useless, disproportionate hands, as if they themselves had become the personifications of the nightmare they are being subjected to. The tireless repetition of the same tattooed concentration camp number seems to perforate each of these drawings except the twenty-fifth, which bears no number at all, perhaps because it is the embodiment of a wordless scream. Collages, penciled webs, retracted lips over horror-grinning teeth, the skull-helmet slipping down again in twenty-seven, where the child's teeth are not shown—the reiterated motifs come together here in a crescendo of simple, unanswerable deprivation.

43⅜ × 39¼ in. | 110.2 × 99.7 cm.

Graphite with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with touches of charcoal, stencil, on card paper

No. 25 (1961-1966)

43 × 429⁄16 in. | 109.2 × 108.1 cm.

Graphite with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine wash, with touches of charcoal, on card paper

No. 26 (1961-1966)

45¼ × 43⅜ in. | 114.9 × 110.2 cm.

Graphite, charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with touches of green pastel (where three stenciled "5,602,715" in green have faded), stencil, and cut, torn and pasted biblical scripture, on card paper, with some torn edges

Collaged excerpts from Deuteronomy 28-32; Joshua 25; Judges 1;1 Samuel 2-4, 6-9, 14-18, 20-21, 23-24, 27-28, 30-31;2 Samuel 2, 9;1 Chronicles 16-17

No. 27 (1961-1966)

43⅞ × 46 in. | 116.5 × 116.8 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, stencil, and cut, torn, and pasted biblical scripture and paper, on card paper

Collaged excerpts from Numbers 20-21, 29-30, 33-34; Deuteronomy 2, 5-7, 12-17, 19, 20-22, 33-34; Joshua 2-3, 8-10, 12-14; Judges 1-12, 20

No. 28 (1961-1966)

82 × 45¾ in. | 208.3 × 116.2 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, stencil, and cut, torn, and pasted biblical scripture and paper, on card paper, with torn edges

Collaged excerpts from 1 Kings 2-4, 10; 2 Kings 8-10, 12-13, 15, 17-18, 19-25; 1 Chronicles 2, 5, 13-14, 19-21, 26-29; 2 Chronicles 1-2, 9-11, 18, 23-26, 32-34; Ezra 2, 5-8; Nehemiah 1, 7, 15; Esther 1-2,5

No. 29 (1965-1966) "It is done, it is finished, but we endure," is what the folded hands and facial expressions in the twenty-ninth drawing seem to be saying. The dark ravaged face of the bishop glares out with an insane defiance, so much at odds with all the composed panels of religious pictures displayed on his shawl—all, that is, except for the one panel where a green money bill glints. The darkness in the bishop's face extends to the cassock of the smug attendant priest grimly wedged into the bishop's left side. The heavy black cassock of the priest momentarily teases the memory until we recall that it is made of the same stuff as the dark webbing of the executioner's gown in the earlier drawings. Then, as if to confirm the association, one notes lying in a pile a frieze of infant corpses on which the clergy are standing. Now the whole composition tingles with a tragic irony which points back to the majestic medieval portraits of saints and church fathers standing on a pediment of lions and wild beasts—the church triumphant! Here the crimson of the priest's sash drips down the children's dead bodies.

77 × 44⅛ in. | 195.6 × 112.1 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with splatters of red wash and touches of green pastel, cut and pasted intaglio print (pope's head and miter hat), tape, biblical scripture and paper, on card paper, two sheets, with torn upper corners

Triptych three panels (1963-1971)

left panel: 79⅝ × 37⅝ in. | 202.2 × 95.6 cm.

center panel: 79⅝ × 44½ in. | 202.2 × 113 cm.

right panel: 79⅝ × 37⅝ in. | 202.2 × 95.6 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, with erasures, brush and asphaltum turpentine, red and white wash, with splatters of red wash, cut, torn, folded, and pasted newspaper, biblical scripture and paper, on card paper, with some torn edges

Collaged excerpts from, left panel: New York Times, May 19, 1963 (articles from Week in Review and business sections, and classified ads); New York Times, August 8, 1965; Cedar Rapids Gazette, May 29, 1967; New York Times, August 13, 1967 (articles from business section); New York Times, August 27, 1967 (articles from Week in Review); and Ezekiel 9, 32, 38; Jeremiah 6; center panel: New York Times, May 19, 1963 (business and sports sections); New York Times, August 13, 1967 (articles from business section, stock exchange trading); right panel: New York Times, May 19, 1963 (articles from sports section)

Triptych follows drawing number 29. The images are intended to be viewed as three panels.

No. 30 (1961-1966)

55⅞ × 29⅞ in. | 141.9 × 75.9 cm.

Graphite and charcoal, brush and asphaltum turpentine and red wash, with splatters of red wash and fingerprints, on card paper, three sheets, with some torn upper edges

A gruesome obiter dictum closes the series in Lasansky's invention of a final irony: a skeleton-mounted Hitler figure in the act of castrating itself faces the spectator. It is like catching the devil cutting off his own tail. Now the blood that drips is the blood of the master executioner—grim, self-absorbed, well-practiced, mechanistically sacrificed to his own ideology, half squatting, cutting off his manhood as the spectre of death clamps down on him the lid-like cover of a bony skull (the last of the skull-helmets), with the decisiveness of someone covering a stuffed garbage can. The artist's upside-down signature beneath it underlies the harshly personal vision of the holocaust so movingly depicted in all the thirty drawings.